Virus and Cancer Connection

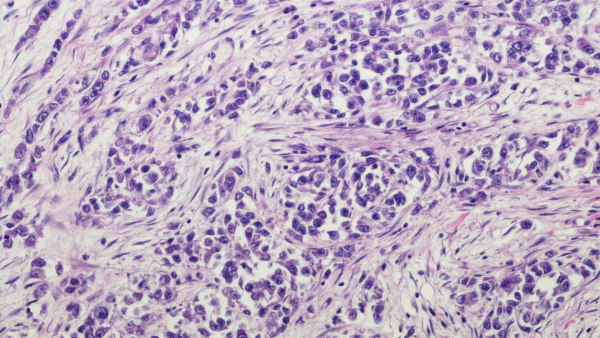

For nearly a century, it has been hypothesized that there is a relationship between cancer and viruses. Over the past decade, concrete molecular evidence has emerged, demonstrating that viruses can indeed cause cancer. In some cancer cells, the virus itself is present, or viral DNA is found integrated into the cell’s DNA. Furthermore, it has been observed that healthy cells grown in the laboratory mutate and begin dividing uncontrollably when exposed to these viruses. This process involves the integration of the viral genetic code into the DNA of the host cell.

The first documented case of a human cancer associated with viruses is Burkitt lymphoma, a type of blood cancer discovered by Denis Burkitt in 1961 in the jawbones of children in Uganda. Inspired by Burkitt’s observations, researcher Anthony Epstein identified a new herpes virus in the diseased cells, later named Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Today, it is estimated that approximately 5–20% of all cancer cases are caused by viruses.

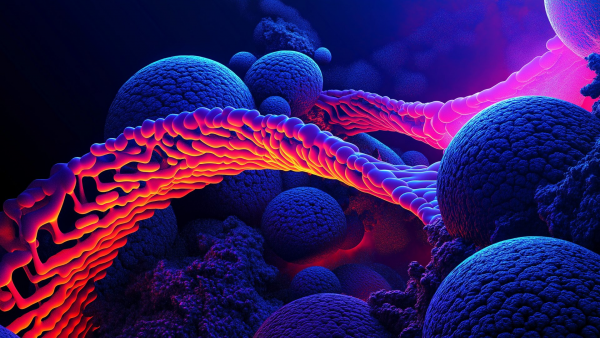

Viruses, in the process of replicating themselves using the host cell’s genetic machinery, can induce changes in the cell’s DNA. These changes accumulate over time, and years after the initial viral infection, they can result in genetic damage. This damage disrupts the cell’s ability to control division and regulatory mechanisms, ultimately leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation and the development of cancer.

One of the most extensively studied types of viruses is retroviruses. These RNA-based viruses, upon entering a host cell, use the cell’s own enzymes to convert their RNA into DNA. This newly formed viral DNA integrates into the host cell’s genome and provides the instructions for the production of new viruses. In rare cases, the viral DNA integrates near specific genes known as oncogenes, which regulate cell proliferation.

This proximity can lead to the activation of the oncogene by the viral DNA, triggering uncontrolled cell growth. Viruses can also cause cancer through other mechanisms, such as carrying their own oncogenes or by integrating into the host genome in a way that stimulates the synthesis of specific proteins, thereby activating the cell’s oncogenes. In addition to retroviruses, DNA viruses such as polyoma, papilloma, adeno, and herpes viruses can also transform cells into cancerous ones. The cancer transformation process typically begins when the viral DNA integrates into the host genome, leading to uncontrolled cell division and cancer formation. Viral DNA can also directly activate oncogenes within the host genome. DNA viruses such as hepadnaviruses may integrate next to specific oncogenes, such as c-myc, triggering cancer development.

The interaction between viral DNA and host DNA can also lead to structural disruptions in the genome, initiating the cancer process. Generally, apart from herpesviruses, the integration of viral DNA into host DNA is considered a random event. The transformation of a cell into a cancerous one as a result of viral invasion is typically the outcome of a series of random errors. Viruses convert infected cells into virus-producing factories, and the changes that occur in the DNA during this process can result in the cell becoming cancerous.